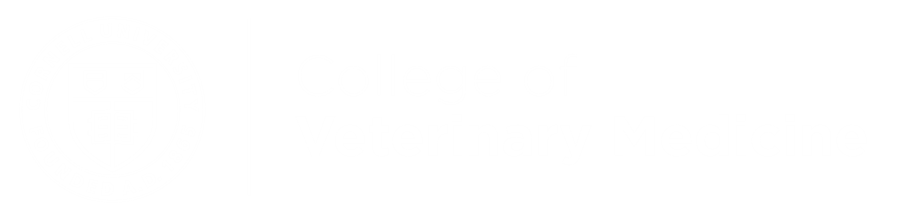

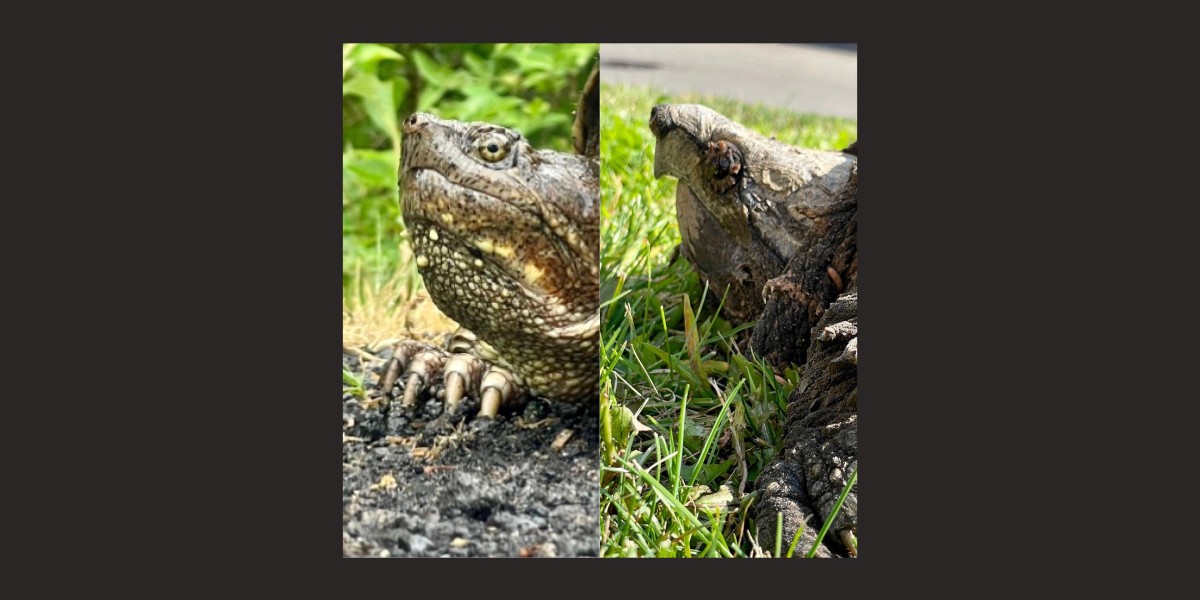

In August of 2023, an alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) was pulled out of the Genesee River in upstate New York by US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) biologists, who were seining (net fishing) for fish. They recognized that she was a different species than our native common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) due to her strongly hooked beak, keeled carapace, and fleshy “eyelashes.” Her species is native to southern and central United States, so this turtle was far out of her normal range and was unlikely to survive long term. Given her presumed hypoxia from an extended stay in the fishing net and the subsequently noted lethargy, she was sent to Cornell’s Janet L Swanson Wildlife Hospital for a health assessment and treatment while New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) biologists evaluated placement options.

When a non-native animal is found on the landscape, we know that it rarely makes its way there naturally. Typically, it is a safe assumption that the animal was a pet that was released or escaped. Alligator snapping turtles (ASTs) are legal to keep in New York, but often people purchase them and become overwhelmed as they grow--and GROW--subsequently becoming difficult to handle and house. Unfortunately, as DEC soon found out, they are equally difficult to rehome, as reputable facilities have specific needs and are often overwhelmed with requests to take in pets that people no longer want. Release is also not an option. Not only is the individual animal unlikely to fare well due to not being able to adapt to temperatures, find food, and evade predators, they also have the potential to negatively impact the ecosystem into which they are released. They can spread exotic parasites or pathogens, prey on or out-compete native species, and increase pressure on species already at risk. The same is true even of native species that have been held as pets--without knowing where they originally came from or what they have been exposed to, they are unfortunately also destined for a continued life in captivity, where they cannot fulfill their important roles in the ecosystem. To prevent this unwanted outcome, all reptiles and amphibians are protected by New York state law and cannot be collected without a permit.

Dubbed “Alfie,” the Genesee River AST got a new lease on life. At the wildlife hospital, she had bloodwork and radiographs and was treated with antibiotics for a respiratory infection. Samples were collected for ongoing collaborative research on the species, as well as genetic analysis. The sample sent to the USFWS was used to help validate eDNA testing for the detection of ASTs in the field, much like that performed here in New York for our own rare and cryptic species. The sample sent to Tangled Bank Conservation was used in a genetic analysis that showed us what river drainage Alfie's lineage hailed from. They pinpointed her origin to the Red River, most likely from Louisiana but with a small possibility of Texas. What could not be determined from this analysis was if she was captive-bred or wild-caught. Tangled Bank noted that multiple breeding facilities pulled turtles from that locale (indicating that she may be captive bred), but also that many poached/confiscated animals come from that area (indicating that she may be wild caught).

As Alfie was recovering, efforts were made to find her a permanent home. Thankfully, a non-profit organization called Texas Turtles, focused on conservation and education, agreed to take her as an ambassador animal. Once she was well, she made the trip to Texas where she continues to thrive under their care. In addition to outreach, Texas Turtles and their collaborators perform mark-recapture studies on ASTs in the wild, looking at trends over time related to life history parameters such as reproduction and survivorship, as well as anthropometric influences such as land use.

After a lot of correspondence about Alfie and turtles in general, CWHL Research Support Specialist, Melissa Fadden, was invited to Texas Turtles “Snapperpolooza,” the biannual AST trapping event. This event provided her the opportunity to participate in boots-on-the-ground population monitoring, reminiscent of her experience as a DEC technician monitoring New York's bog and Blanding’s turtles. Throughout the three-day event, six ASTs were captured, including five “new” animals and one that had been caught in previous years, adding to a total of 30 ASTs at this survey site. All animals had data taken--measurements, weight, lure color, and notable characteristics like wounds described. Adult females received an ultrasound, performed by longtime collaborator the Environmental Institute of Houston at the University of Houston-Clear Lake, to assess their reproductive status. Once processed, all turtles were released safely at the point of capture. We also had the pleasure of seeing a vast variety of other Texas herpetofauna. Additionally, Fin and Fur Films crew was on site, capturing footage of the turtles for an upcoming documentary. While this added yet another layer of fun, it is also of greater significance than mere entertainment--knowledge fosters appreciation, so ideally the result will strengthen the connection between people and these lurking leviathans.

Conservation happens through research and response, with ongoing, painstaking data collection and analysis, entrenched in muddy boots and piles of paperwork. A critical piece of the science puzzle that is often overlooked is that conservation happens through partnerships and advocacy, on truck tailgates and over campfires, through intertwined worlds, and through simple passion.