A Research Support Specialist: Melissa Fadden

My role within the lab is a complex balancing act of time management, project and sample organization, and managing our case data stream. I guide incoming diagnostic case submissions, manage research project samples and submissions, and help facilitate educational activities like wet labs and symposiums. It’s a job where I clock a few miles daily just within our building, more when I get to sneak out for some beloved fieldwork. Each day is vastly different depending on the time of year, current projects, and diseases active on the landscape. It involves coordination and collaboration among outside agencies and internal lab sections, data management on the computer, a bit of lab work, a touch of necropsy and tissue harvest, a fair amount of driving, and my favorite part, a lot of learning (and teaching!), no matter how long I’ve been here.

7:17 am: Alarm goes off. Begrudgingly remove the sleepy cat from my face (the other is already downstairs begging for breakfast), get up, get dressed, let the dog out, and throw a lunch together.

7:37 am: Out the door. A 20-minute commute gives me just enough time for an NPR episode (Up First or Life Kit) or a few punk songs to get jazzed for the day.

8:00 am: Arrive at work and make some coffee. Eat my breakfast as I sort emails. A large portion of my job is managing our diagnostic caseload--animals submitted to find cause of death. Results from these cases come from the AHDC pathologists and labs (Virology, Parasitology, Molecular Diagnostics, Bacteriology, Toxicology) via email, so my first order of business is always to ensure that time-sensitive results are addressed and disseminated. I’ll return to the non-pressing ones later to enter them into our database, which in turn feeds the website where our DEC biologists can access their case updates.

8:41 am: The wildlife hospital messages me. They have a choanal (bird nasal cavity) swab from a Canada goose that they want to drop off for avian influenza testing. The bird is alive and in isolation. The sample is a priority to run STAT, so they receive same-day results and can plan diagnostics and treatments accordingly while keeping their other patients safe.

9:18 am: The wildlife hospital staff drops off the sample at the AHDC; I deliver it with the associated paperwork to the Receiving Department to be transferred to the Molecular Laboratory. While I was there, Receiving gave me excess bobcat blood that was returned from Clinical Pathology. The blood came from a wild bobcat that is part of a population study. A health assessment was done and included a complete blood count and a chemistry panel (just like they run on humans). Since it's a sample type that we don't often collect, it is valuable to keep the excess sample, so I spin it in the centrifuge and pipe the plasma into vials for long-term storage. I deliver the vials to the wildlife lab freezer and trot back to my desk just in time for our group Zoom meeting.

10:00 am: CWHL team meeting, where our tight-knit, but geographically scattered, group updates everyone on what they’re working on and how we can be of assistance to one another.

11:00 am: Meeting has adjourned, and I see that I missed a call from Receiving--samples from our Wildlife Health Unit colleagues have arrived. I collect them, enter them into our lab system to submit testing requests, and then start labeling them. I'm interrupted by my phone ringing. It’s Necropsy staff; they have a DEC Environmental Conservation Officer at the door delivering a bald eagle that was found deceased.

11:42 am: Cruise down to Necropsy, have a nice chat with the officer before he departs, and place the eagle in the walk-in cooler. Head back upstairs to my desk, fill out paperwork for the new bird, finish labeling the morning samples that have been waiting for me in the lab fridge, and then head back downstairs to deliver the samples to Receiving for distribution throughout the building to the appropriate lab sections for testing. While I'm down there, I label the eagle with its new patient ID and accession number (how we keep track of it within our database and the lab).

12:15 pm: Stomach growling, I dig out my sweet potato curry and scarf it down--I’m expecting a delivery from a DEC biologist around 1:30, but want to get some research samples submitted before that. While I’m eating, I create an event for a hiking group I’m in for the upcoming weekend (needs to be Sunday, because Saturday is spay/neuter clinic volunteer day). My lunch and weekend dreaming are interrupted by the phone again, this time a wildlife rehabilitator who wants to run an unusual case by me to see if it falls within our specimens of interest for testing. It is a juvenile red fox with a head bobble. Usually, a single individual of a common species wouldn't fall under our specimens of interest, but avian influenza has been showing up in red foxes, so I agree to send her a cooler to ship the body to us for evaluation.

1:20 pm: The DEC biologist calls to let me know she has arrived with the specimens for me. I drop off the fox cooler at the Shipping department to be mailed out and continue to Necropsy to accept the biologist's submissions: a red-tailed hawk, three crows, and a bag of lymph nodes from recreationally harvested white-tailed deer for routine chronic wasting disease surveillance. The animals join the eagle in the queue for necropsy, and I deliver the lymph nodes to Virology for testing.

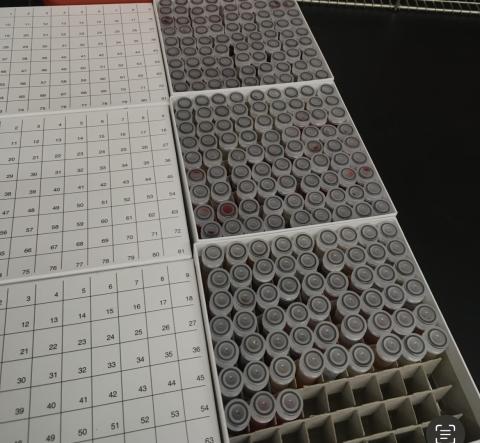

1:40 pm: Pull 81 serum samples from white-tailed deer from our freezer to submit for EHD testing in support of a project we are collaborating on with a Ph.D. student. EHD outbreaks appear sporadically in New York, with large mortality events in 2020 and 2021. Deer in southern states often survive an infection, but not much is known about immunity in our herd. This project aims to address that knowledge gap.

2:30 pm: Finish paperwork for the necropsy specimens, return to the reports from earlier in the day that weren’t time-sensitive, and pull data from the database for a West Nile virus retrospective study that a pathology resident is undertaking. Our database holds details on each submission since the inception of the Wildlife Health Program in 2011. We can look up information like animal age, sex, location, finder/submitter, all of the testing that was performed, and the cause of death if identified. We can use this information to look at trends over time--increases in prevalence of certain diseases, geographic or species spread, etc.

3:45 pm: Check on goose results. Avian influenza was not detected. I message the hospital, who will be happy to hear this.

3:50 pm: Water desk plants. Write a sticky note for tomorrow’s tasks: take biological lab waste to the drop-off location for safe disposal, pull the list of 2023 cases from the database, submit the License to Collect and Possess for the program (a legal requirement to be able to handle the native animals that we do), pull fisher livers from our tissue archive with a vet student for a project evaluating rodenticide and lead toxicity in carnivores, thaw starlings for an upcoming lab on bird anatomy, construct more sampling kits for a cervid testing effort shared with NYSDAM, and outline a presentation on reptile and amphibian pathogens and parasites that I’m giving for an upcoming meeting with DEC.

4:20 pm: Home! Play fetch with the cats, stroll down the rail trail (often catching a glimpse of live eagles and other wildlife like muskrats, which brings me joy after working with the deceased all day), fit in a little herping or foraging if the season is right, tidy the house or play in the garden.

7:00 pm: Partner arrives home, we eat dinner, and I wind down with a book, some jewelry making, or an episode of something short and comedic.

10:00 pm: Bed, in preparation to repeat!

I appreciate how diverse my job is and the opportunities that are afforded me in support of my position. As a biologist by trade with many years in the vet world, this role is the perfect culmination of skill sets and interests, in a capacity that allows for continued personal and professional growth, as well as flexibility to pursue interests that align with my work. I love being in the field, looking for endangered turtles, deep-diving into old datasets or freezer bins, and contemplating our place in the world amid the wildlife that we are charged with keeping secure.