Have you ever wondered how some people avoid getting sick even when they’re surrounded by sick people? Disease can seem pretty random- either you catch a bug from your coughing friend, or you get lucky and stay healthy. Though chance may have some role in determining whether a person or animal gets sick, there are many other factors at play.

Infectious disease is often represented by a triangle consisting of a host (the plant or animal that can get a disease), a pathogen (the disease-causing agent), and the environment (the location and conditions that bring the host and pathogen together). This triangle can be expanded to include the microbiome (bacteria living on the host). For disease to occur, you need a “perfect storm” of interactions among these components: 1) a host that is susceptible to infection, 2) a pathogen that can cause disease if it infects the host, 3) a microbiome that allows infection to occur, and 4) environmental conditions that support the host, pathogen, and microbiome. With this many moving parts, it can be really complicated to understand why disease occurs in some hosts, but not in others.

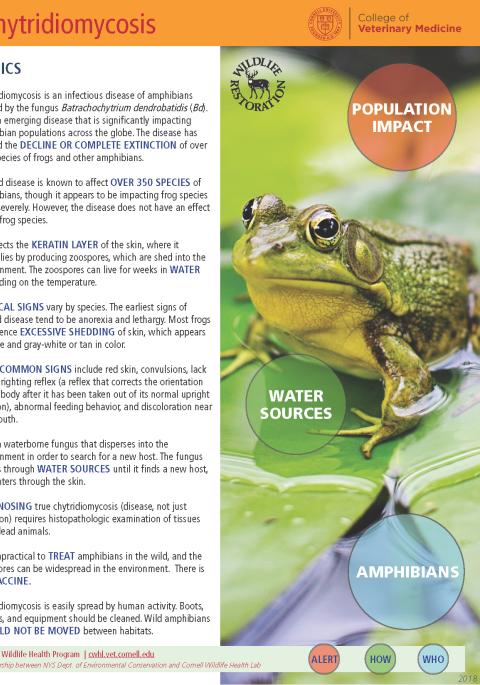

In 2014, previously healthy captive-reared eastern hellbender salamanders were dying of a skin disease called chytridiomycosis after being released into New York streams to boost the resident population of healthy animals. Wild hellbenders are often infected with Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), the fungus that causes chytridiomycosis, but these animals almost always show no signs of disease. Why were the captive-reared animals dying from something wild animals tolerate? Were they missing some form of immunity that wild hellbenders got from growing up in streams that contain Bd?

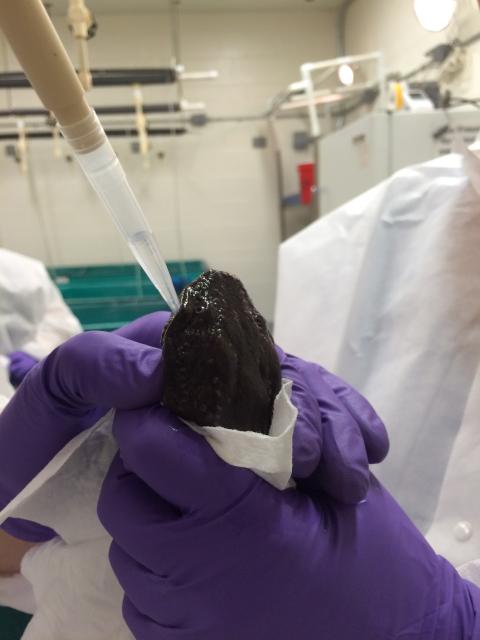

We designed a vaccination and infection experiment to study the interaction of host, pathogen, and microbiome. With the hope of improving survival in released animals, we needed to understand how wild hellbenders survive Bd infection, but captive-reared animals become diseased. Captive-reared hellbenders were given a series of one of three vaccination treatments: 1) oral vaccination with killed Bd, 2) topical vaccination with killed Bd, or 3) mock vaccination with saline, administered four times over 63 days. A few weeks after the final vaccination, we exposed the animals to live Bd and monitored disease progression, expression of immune genes in their skin, and the composition of other microbes living on their skin for 135 days.

We found that vaccinated and unvaccinated animals developed disease at the same rate and intensity; there was no protective benefit from the vaccine. However, the oral vaccine activated an immune response in the skin more than the topical vaccine did. This result suggests that hellbenders have an acquired immune response to Bd, although it did not protect the study animals from disease. During infection, Bd function changed dynamically to better enable the fungus to cause disease. The community of bacteria living on hellbender skin did not provide any protection against Bd infection or disease; instead, the microbial community structure itself was changed by infection and disease.

This experiment is the first to examine gene expression over time in the host, pathogen, and microbiome. Although the study failed to identify a protective vaccine, our results shed new light on the amphibian disease system in a chytrid-tolerant species of conservation concern. The complete article is openly accessible (link below).

Kaganer AW, Ossiboff RJ, Keith NI, Schuler KL, Comizzoli P, Hare MP, Fleischer RC, Gratwicke B, Bunting EM. 2023. Immune priming prior to pathogen exposure sheds light on the relationship between host, microbiome and pathogen in disease. R. Soc. Open Sci. 10:220810. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.220810