West Nile Virus (WNV) is an arbovirus (a mosquito-borne virus) of the genus Flavivirus. It infects over 250 species of birds, but corvids (crows, blue jays, and ravens) are the most susceptible to dying from the disease.

Most mammals can become infected but usually do not develop clinical disease. Horses represent approximately 97% of all reported non-human mammalian cases of WNV. The majority of cases are reported during the summer months when exposure to mosquitoes is high.

Clinical signs exhibited in birds that become infected with WNV include loss of coordination, head tilt, tremors, weakness, and apparent blindness. Some species are more resistant to WNV than others, with crows and raptors being

highly susceptible.

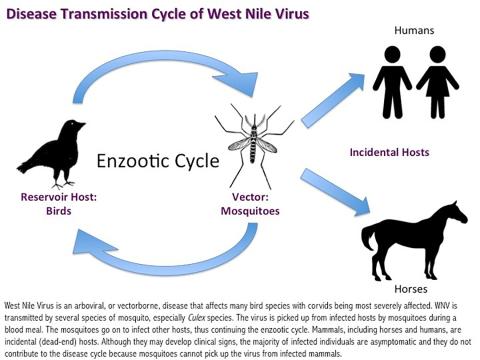

Mosquitos become infected with West Nile Virus when they take a blood meal from a bird that is carrying the virus. Mosquitos then transmit the virus to other birds during subsequent blood meals, continuing the cycle.

Several laboratory tests can diagnose WNV; preferred tissues for testing include heart, brain, and kidney. Oral swabs can detect virus DNA in crows but are not usually effective in other species.

WNV is treated with supportive care. Vaccines are available for birds and horses, but not humans.

In order to prevent the spread of WNV, measures such as mosquito vector control and limiting exposure to mosquito bites should be practiced. Eliminating the breeding habitat helps reduce mosquito populations. Mosquitoes lay eggs in water, so removing standing water in and around homes can help reduce mosquito larvae.

Voluntary mosquito surveillance is performed by some local health departments. It begins in early summer, and mosquito pools from traps are collected weekly and tested for multiple diseases.

The first cases of WNV were detected in New York City in 1999. It has since spread throughout the continental United States and beyond.

Human cases vary considerably from year to year, from 712 cases nationwide in 2011 to 5,674 cases in 2012. Environmental factors, including rainfall, temperature, and mosquito vectors, all play a role in the varying case numbers.

Other mammals in which the virus has been detected include squirrels, chipmunks, mice, rats, and other rodents, as well as skunks, canids, white-tailed deer, raccoons, bears, opossums, bats, and non-human primates.

Mammals are usually asymptomatic or will have flu-like illnesses, including fever, headache, tiredness, body aches, nausea, and vomiting. Neurological signs and encephalomyelitis (inflammation of the brain and spinal cord) occur in a small proportion of horses and humans infected with the disease. This form of the disease can be debilitating and cause permanent central nervous system damage and possibly death.

The case fatality rate for horses exhibiting clinical signs is approximately 33%. Less than 1% of humans bitten by infected mosquitos become severely ill. The risk of severe disease is highest in individuals with compromised immune systems and individuals over the age of 50 or under 15.

Culex species of mosquitoes commonly carry WNV. When a species of mosquito that bites both birds and mammals becomes infected, there is the potential for transmission to incidental hosts.

Humans and horses are most likely to develop clinical illnesses. They are considered dead-end hosts because although they can become infected, the number of viral particles in the blood is not high enough to pass the virus on to new mosquitoes.

Direct bird-to-bird transmission of WNV is possible, although not as significant as vector-borne (mosquito) transmission. Oral secretions and feces from infected birds can contaminate food or water and potentially spread the virus from bird to bird. Raptors that prey on infected birds can acquire the virus by ingestion.

Squirrels, chipmunks, and raccoons have been shown to shed the virus in oral secretions, feces, and/or urine. In humans, WNV has been transmitted in a small number of cases by organ transplants, blood transfusions, and breast milk. Direct contact between people and animals is not a known source of infection to humans.

There is no specific treatment for the virus, only supportive care

Areas of standing water mosquitos lay eggs in include wheelbarrows, pool covers, birdbaths, gutters and any other place water can collect. Pool and pond water can be treated with mosquito dunks, which contain a natural bacterial product that kills mosquito larvae.

Mosquitoes should be prevented from entering the home through open windows and doors or broken screens. Personal preventive measures include limiting skin exposure by wearing shoes, socks, long sleeves, and pants, especially during times when mosquitoes are most active, like dusk. Exposed skin can be protected with mosquito repellent. Local county health departments are responsible for general mosquito control measures in New York.

There is a WNV vaccine available for horses, and it is a recommended core vaccine by the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP). This vaccine is also used in captive birds.

West Nile Virus is established across New York State. The NYS DEC Wildlife Health Program will routinely test for WNV on submitted cases during the summer and fall. Veterinary surveillance for encephalitis in horses is encouraged.