Salamander chytridiomycosis is an infectious disease caused by the fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal). The fungus is a close relative of B. dendrobatidis (Bd), which was described in 1998 and is responsible for the decline or extinction of hundreds of species of frogs and toads. Salamander chytridiomycosis, and the fungus that causes it, were described in 2013.

Once introduced, the fungus is capable of surviving in the environment, in the leaf litter and small water bodies, even in the absence of salamanders.

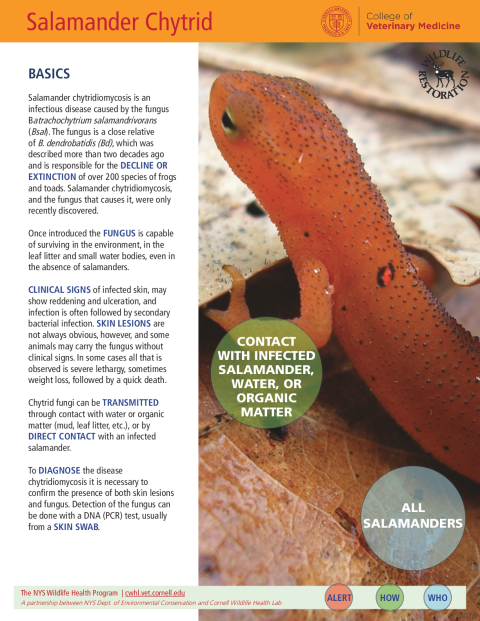

Clinical signs of infected skin may show reddening and ulceration, and infection is often followed by secondary bacterial infection. Skin lesions are not always obvious, however, and some animals may carry the fungus without clinical signs. In some cases, all that is observed is severe lethargy, sometimes weight loss, followed by a quick death.

Chytrid fungi can be transmitted through contact with water or organic matter (mud, leaf litter, etc.), or by direct contact with an infected salamander.

To diagnose chytridiomycosis, it is necessary to confirm the presence of both skin lesions and fungus. Fungal detection can be done with a DNA (PCR) test, usually from a skin swab.

The first cases occurred in The Netherlands, as outbreaks in native fire salamanders, Salamandra salamandra. Further work discovered that the fungus is present in Thailand, Vietnam, and Japan, and originated in native Eastern Asian salamanders without causing significant disease. Evidence suggests that the fungus was introduced to Europe more recently, probably through imported pet salamanders that can act as carriers.

Experimental trials on 35 North American amphibian species across 10 families showed that 75% of species can become infected, and 35% of species experienced mortality from Chytridiomycosis including the widespread Eastern newt (Notophthalmus viridescens).

Susceptibility varies by species, ranging from resistant to highly susceptible to mortality; within this spectrum, researchers predict the loss of up to 140 North American amphibian species.

If B. salamandrivorans is introduced into North America, it will likely become permanently established and, based on experience with frog chytridiomycosis, will be impossible to eradicate.

The disease is not yet confirmed in North America, but the introduction of the fungus into native salamander populations could have devastating effects. North America has the greatest diversity of salamander species in the world. In Europe, the fire salamander population where the disease was first discovered is at the brink of extirpation, with over 96% mortality recorded during outbreaks.

The fungus produces motile zoospores, capable not only of surviving in water and moist environments, but also of short distance dispersal through active swimming. Because the fungus and its infectious zoospores can survive in the absence of an infected host, transmission from an outbreak site to adjacent areas can occur both through dispersal of infected salamanders and through human activities, such as movement of soil, water or even fishing bait.

Infection (presence of the fungus in a host) and disease (ill effects on the host) are not the same thing. Some salamander species, such as East Asian species that coevolved with the fungus, can be infected but do not develop disease. Confirmation of the fungus in skin sections, along with evidence of skin damage, is necessary to confirm the disease.

Antifungal drugs and heat treatment could prove effective against the salamander chytrid fungus in captive individuals.

As with frog chytrid fungus, salamander chytridiomycosis could be spread during anthropogenic activities. Boots, clothes, and all field equipment should be cleaned with a 10% bleach-water mixture before moving between sites. Pet salamanders should never be released to the wild. Water used in captive enclosures should never be dumped outside on the ground.

Wild amphibians should not be moved between habitats, and captive animals should not be used as fishing bait.

All newly acquired captive amphibians should be initially quarantined from other amphibians until it has been confirmed that they are disease-free by serial lab tests.

Suspicious deaths of salamanders both in the wild and in captivity should be reported to enable early detection of this disease.