Hemorrhagic disease (HD) is a general term for illness caused by two related viruses: Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease virus (EHD) and bluetongue virus (BT).

HD primarily affects white-tailed deer and can cause significant mortality events, particularly in the northern United States. Mule deer and pronghorn antelope are also affected. Domestic ruminants (sheep, cows, goats) are also susceptible to HD. Cows typically do not show clinical signs, but sheep can suffer severe disease and death from BT infection. Neither EHD or BT are a disease of humans.

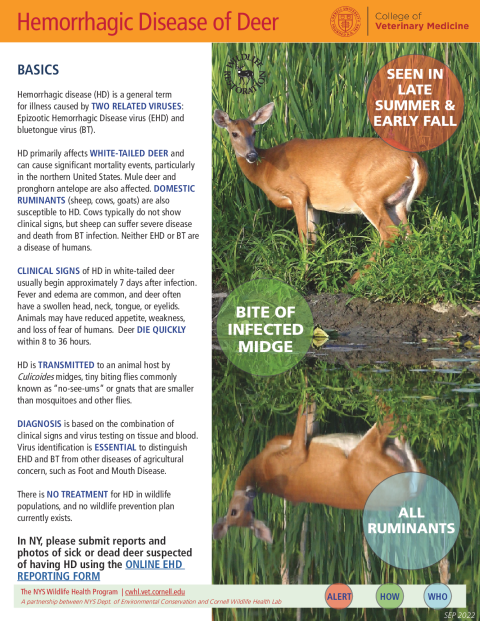

Clinical signs of HD in white-tailed deer usually begin approximately 7 days after infection. Fever and edema are common, and deer often have a swollen head, neck, tongue, or eyelids. Animals may have reduced appetite, weakness, and loss of fear of humans. Deer die quickly within 8 to 36 hours.

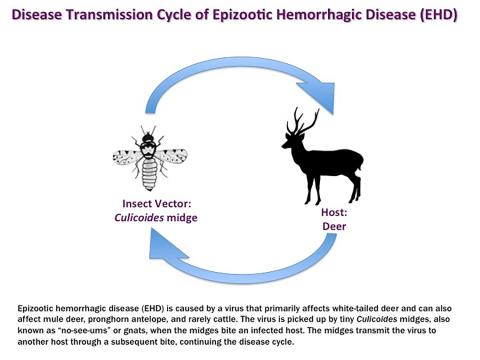

HD is transmitted to an animal host by Culicoides midges, tiny biting flies commonly known as “no-see-ums” or gnats that are smaller than mosquitoes and other flies.

Diagnosis is based on the combination of clinical signs and virus testing on tissue and blood. Virus identification is essential to distinguish EHD and BT from other diseases of agricultural concern, such as Foot and Mouth Disease.

There is no treatment for HD in wildlife populations, and no wildlife prevention plan currently exists.

In NY, please submit reports and photos of sick or dead deer suspected of having HD using the Online EHD Reporting Form.

Both EHD and BT are in the genus Orbivirus and family Reoviridae. There are 10 known serotypes (variations) of EHD and 24 serotypes of BT worldwide. Outbreaks of EHD in domestic ruminants are becoming more common.

HD produces lesions on the mouth and feet that resemble a serious viral disease of livestock called Foot and Mouth Disease which is not currently found in the US. BT can potentially infect domestic dogs.

Clinical signs of HD infection in deer vary based on the serotype and whether or not animals have any preexisting immunity. The incubation period ranges from about 5 to 10 days. The acute form of HD has high mortality rates. Fever causes deer to seek out water, so dead deer may be found near or in water. Deer with chronic infections may show hoof abnormalities, including sloughing of hoof walls.

The viruses damage the endothelium, the lining of the blood vessels, causing small hemorrhages throughout the body. Hemorrhage in the heart and lungs can result in respiratory distress. There may be dental pad erosion or tongue ulcers as well as bloody discharge from the nasal cavity. Ulcers of the stomach (rumen and omasum) may also be present.

HD causes high mortality in northern deer with little preexisting immunity. In domestic ruminants, such as cattle and sheep, HD is usually less severe but may cause fever, oral ulcers, and other mild signs. Sheep are especially susceptible to BT and can suffer severe disease and death.

Transmission of HD occurs when a female Culicoides midge picks up the virus from the blood of an infected host and then transmits the virus by biting another host.

Laboratory tests that can confirm HD include immunofluorescence and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests from tissues or blood.

HD outbreaks occur in late summer and early fall when insect vectors are active. The midges and viruses are killed within two weeks of the onset of frost ending the transmission cycle. Although the vector is not found in all areas, it is easily transported to new areas by wind currents.

EHD and BT have circulated in the southern United States for decades and outbreaks in deer there are typically mild or completely inapparent, detectable only by antibody titers. The periodic movement of infected midges in recent years to the northern United States where there is little history of previous exposure results in severe outbreaks with high mortality.

EHD was confirmed in New York State in October 2007. In August 2011, an outbreak of EHD caused an estimated 100 deer mortalities in Rockland County before Hurricane Irene ended the episode.

In the early fall of 2020, another large outbreak occurred in the lower Hudson Valley and killed an estimated 1,500 deer. In 2021, reports of dead deer in New York started in July. This outbreak resulted in nearly 2,000 reports of dead deer with positive cases of EHD confirmed in 15 counties in the Hudson Valley, the Great Lakes region, and Long Island. Serotypes EHDV-2 and -6 were detected in 2021. Thus far in 2022, only EHDV-2 has been detected in New York.

In the late summer of 2022, BT virus was detected in New York deer for the first time, in addition to cases of EHD.

HD outbreaks do not have a significant long-term effect on deer populations, but deer mortality can be intense in small geographic areas.

Although New York State does not actively conduct surveillance for the viruses, sightings of sick or dying deer or groups of dead deer should be reported to the nearest DEC regional wildlife office. DEC provides a list of regional DEC office contacts.

With the help of the Wildlife Health Program, the DEC launched a new online reporting system in 2021 to handle the large number of incoming reports.