As a wildlife disease ecologist, I’ve been asked my opinion on the scientific support for prions as the agent of chronic wasting disease (CWD). I have been studying CWD for two decades. The spiroplasma (bacteria) theory1 has been around for years, but has recently resurfaced. I’ll lay out the many reasons why prions are implicated in all transmissible spongiform encephalopathy diseases (TSE). No other infectious agent has the same amount of evidence.

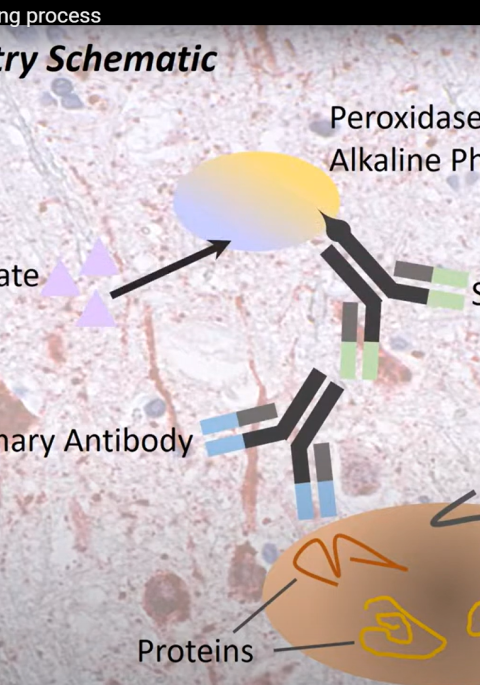

First off, what is a prion? Dr. Stanley Prusiner first described prions in 19822 and coined the term prion as shorter version of “proteinaceous infectious particle.” [Smart guy - he won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1997.] A prion is a cellular protein normally produced by all mammals. In this normal form, prions are relatively unstable and are broken down quickly by proteases (enzymes that break down proteins and peptides). Disease happens when the protein changes shape and are no longer broken down by proteases. Prions ends up clumping together and poisoning brain cells, causing them to die and form holes in the brain3.

There are many different TSE diseases. Some are genetic and happen along familial lines, some apparently occur spontaneously (ex. Creutzfeld-Jakob disease in humans), some are caused by feeding behavior (ex. “mad cow” disease), but scrapie in sheep and CWD in deer, elk, moose, and reindeer are the only two TSEs that are contagious (i.e., transmissible via contact). All prion diseases have several characteristics in common that do not fit with a bacteria or virus as the source of the infection.

Lines of evidence:

1. There is not an immune response to CWD like other disease agents4.

When a foreign virus or bacteria enters the body, the immune system starts to fight it. There is inflammation and fever. The body produces antibodies to the disease agent. We do not see these processes in CWD.

2. Prions are resistant to normal disinfection procedures that kill bacteria and viruses.

Prions can withstand high temperatures, radiation, and chemicals (including formalin) that would normally kill bacteria and viruses. Commonly used methods, such as autoclaving, decreases infectivity but does not completely eliminate it. Harsh chemicals, like bleach, must have an extended contact time to break down the protein.

3. Prions can last in the environment for years.

Multiple studies looking at CWD and scrapie have attempted to “clean” pastures and then restock with animals5. This involves decontaminating all equipment or structures and leaving the area fallow for two or more years. Invariably, new animals end up becoming diseased because prions can bind to steel and soil particles, where they remain infectious. Scrapie persisted in infected sheep paddocks in Iceland for at least 16 years6.

4. Genetic studies have shown that “knock-out” animals that do not produce normal prions do not get TSEs.

Genetically engineered animals that lack the prion gene have been produced in a variety of species from mice to cattle. These animals do not produce normal cellular prion protein, and therefore, are not susceptible to TSEs7.

5. Synthetic “artificial” prions have been created and they cause TSE-like disease.

Most studies use brain material as the source of prions for infection trials, which could potentially transfer other disease agents. However, researchers created prions in E. coli bacteria and produced disease in mice, which is compelling evidence that prions are infectious proteins8.

6. Bacteria have not been identified in diseased animal tissues using a variety of testing methods9,10. DNA or RNA from a virus or bacteria has not been identified consistently in diseased animals.

Examining infected tissues under a microscope has not demonstrated that bacteria are present. If spiroplasma was the cause, genetic sequencing should be able to find the DNA or RNA for that bacteria in samples. Highly sensitive tests used only to amplify proteins has generated infectious prions11. Originally, Dr. Prusiner examined scrapie and found if he inactivated all DNA or RNA in the source material, when he infected experimental animals they still ended up diseased. If he got rid of all the proteins in the source material, the disease agent was no longer infectious2.

While prions still are challenging and there is still plenty to be learned, we would be taking a step backwards in the fight against CWD if we are distracted by nay-sayers. Hundreds of scientists are investigating prion diseases. The evidence is compelling.

“Based on the available data, the idea that prions consist of viruses or any other type of conventional micro-organism is simply untenable” Soto 201112. “These findings have proven beyond any doubt that the prion hypothesis was indeed correct. This does not mean that everything is known regarding prions. On the contrary, there are many outstanding questions still unanswered.”

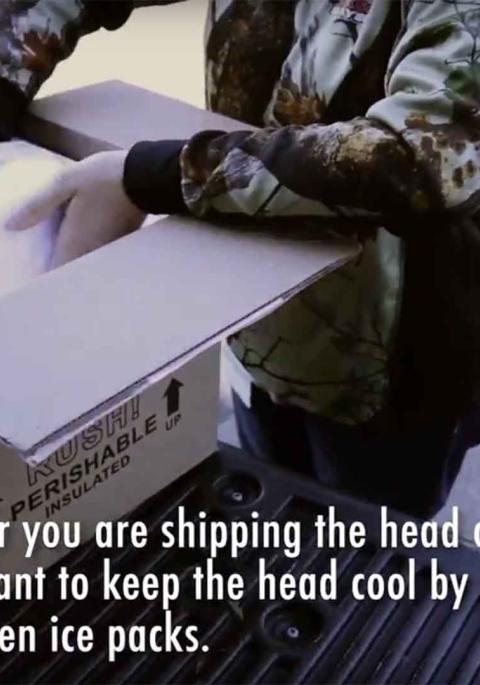

While the public may become frustrated with the unanswered questions around CWD, the one thing we should agree on is stopping prions from being introduced to new areas. Prevention is our best strategy.

While this is not a comprehensive list of literature, it does provide background on some key points if you are interested in learning more:

- Bastian FO. The Case for Involvement of Spiroplasma in the Pathogenesis of Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies. 2014;73(2):104-114.

- Prusiner SB. Novel Proteinaceous Infectious Particles Cause Scrapie. 1982;216(April).

- Sigurdson CJ, Aguzzi A. Chronic wasting disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772(6):610-618. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.10.010.

- Zabel MD, Avery AC. Prions — Not Your Immunologist’s Pathogen. 2015:1-7. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004624.

- Hawkins SC, Simmons H, Gough KC, Maddison BC. Persistence of ovine scrapie infectivity in a farm environment following cleaning and decontamination. Vet Rec. October 2014:1-5. doi:10.1136/vr.102743.

- Georgsson G, Sigurdarson S, Brown P. Infectious agent of sheep scrapie may persist in the environment for at least 16 years. J Gen Virol. 2006;87(12):3737-3740. doi:10.1099/vir.0.82011-0.

- Richt JA, Kasinathan P, Hamir AN, et al. Production of cattle lacking prion protein. 2010;25(1):1-15. doi:10.1038/nbt1271.Production.

- Legname G. Synthetic mammalian prions. 2014;673(2004). doi:10.1126/science.1100195.

- Alexeeva I, Elliott EJ, Rollins S, Gasparich GE, Lazar J, Rohwer RG. Absence of Spiroplasma or Other Bacterial 16S rRNA Genes in Brain Tissue of Hamsters with Scrapie. 2006;44(1):91-97. doi:10.1128/JCM.44.1.91.

- Hamir AN, Greenlee JJ, Stanton TB, et al. mirum and transmissible mink encephalopathy (TME). 2011:18-24.

- Kim J, Cali I, Surewicz K, et al. Mammalian Prions Generated from Bacterially Expressed Prion Protein in the Absence of Any Mammalian Cofactors. 2010;285(19):14083-14087. doi:10.1074/jbc.C110.113464.

- Soto C. Prion Hypothesis: The end of the controversy? 2012;36(3):151-158. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2010.11.001.Prion.