Wild turkeys are a conservation success story in New York state. Due to overhunting and loss of forest habitat to small farms, turkeys disappeared for over 100 years until a small population wandered over the border from Pennsylvania into Western New York in the 1940s. Over the next decade the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) repopulated turkeys across the state through both captive breeding and relocation of birds from successful flocks. After recovering to a high of around 300,000 birds in 2001, the population has been progressively declining over the past ten years to only 160,000 birds. Thanks to research by Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, SUNY College of Environmental Science and the NYSDEC, we may now know one of the reasons why: Lymphoproliferative Disease Virus, or LPDV.

LPDV can cause tumors to form in the spleen and liver of infected young turkeys, and was first discovered in the United States in 2009 by a team of researchers at the University of Georgia. Realizing the dangers LPDV posed to New York’s turkey population, The Cornell Wildlife Health Lab (CWHL) partnered with the NYSDEC to begin a wildlife disease surveillance.

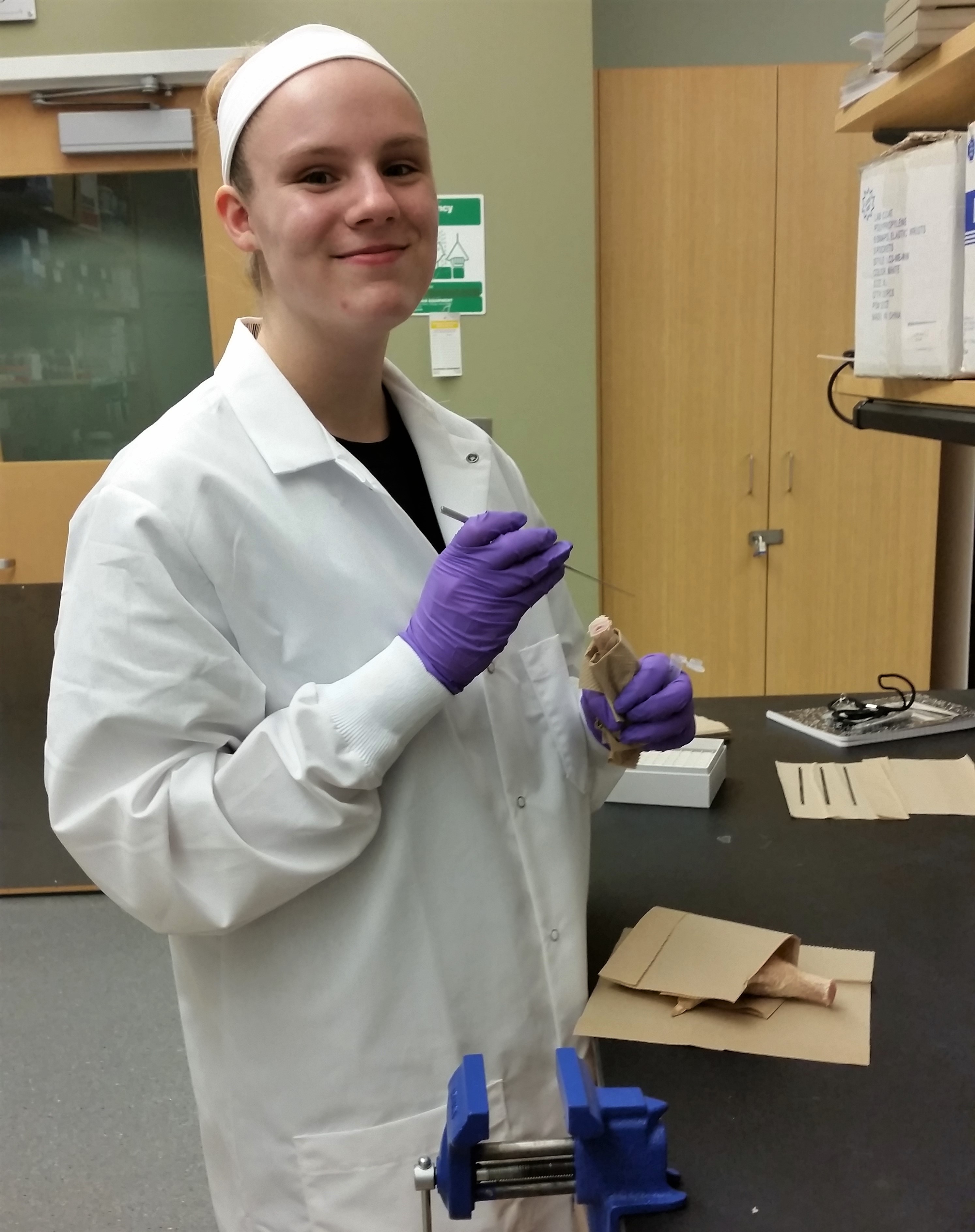

NYSDEC biologist Joe Okoniewski, who specializes in examining wildlife for signs of diseases and toxins, devised an ingenious plan for finding out if New York turkeys were infected. Every year hunters submit the feet from their birds so that the state can collect information on harvest numbers, sex, and age. He realized that the small amount of bone marrow remaining in these turkey legs could be tested for the virus. The CWHL partnered with the NYSDEC to collect turkey legs and shipped them to the University of Georgia for a rapid survey.

The group quickly realized that the virus was widespread in New York, with every county testing positive. In addition, tests from other states concluded the virus had spread to 17 states. It was puzzling though, since newly introduced diseases don’t typically spread so far so fast, and few birds were showing up sick with tumors. In fact, most of the infected birds appeared to be perfectly healthy. (Molecular Surveillance for Lymphoproliferative Disease Virus in Wild Turkeys {Meleagris gallopavo} from the Eastern United States).

Next the group teamed with Katrina Alger and Chris Whipps at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, to study the ecology and possible origins of the virus.

Alger examined over 2,500 wild turkey legs from healthy hunter submitted birds and found 81 percent of the adult female birds were infected with LPDV, and more than half of all wild turkeys tested in New York carried the virus. By comparing the similarities between the virus samples that she recovered and tracing bird movements from the old repopulation project, Alger also determined that it was likely humans moved the virus around undetected decades ago (Risk factors for and spatial distribution of lymphoproliferative disease virus (LPDV) in wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo in New York State, USA).

Based on this cooperative approach, it doesn’t seem that LPDV is in fact “new,” highly lethal, or solely responsible for the recent declines in the turkey population. However, similar viruses in domestic chickens and turkeys can suppress the immune system and make birds vulnerable to other infections.