Solving the mystery of wildlife mortality with diagnostics

When the Cornell Wildlife Health Lab investigates mortalities in wildlife, our specially trained pathologists use diagnostic tools to crack the case. Our pathologists are veterinarians who have completed at least three additional years of specialty training in the diagnosis of disease after animals have died. One of the key diagnostic tools they are trained to use is histopathology, often referred to as "histo" for short. So what is histopathology, you ask? Simply put, it's the examination of tissues under a microscope.

Searching for clues

Domestic animals usually come with a full history and description of clinical signs that help the pathologist plan diagnostic testing and determine the cause of death. Unfortunately, wildlife doesn't often come with any information and that makes them harder to sort out. When a wild animal case is submitted to the lab, a pathologist carefully examines the body both inside and out (think autopsy but for animals). This first exam is called a "gross" necropsy- looking for obvious evidence of disease or injury.

Getting answers under the microscope

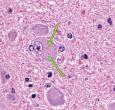

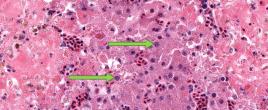

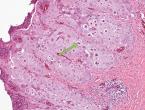

Pathologists collect samples from all the different organs during the necropsy, particularly if they see anything unusual. These tissues are treated with the chemical formalin- a process called "fixation" --to prevent any deterioration, then they are embedded in paraffin wax so that they can be sliced thin on a special machine called a microtome. These very, very thin slices of tissue are put on glass slides and colored with a standard stain (called H&E) that turns them pink and purple so that the cells and any viruses, bacteria etc. can be identified under the microscope.

Looking even closer

Microscopic damage caused to the tissues from infectious agents or "pathogens," can follow characteristic patterns. Lesions caused by bacterial infections for instance are different from lesions due to a viral or parasitic disease. Using high magnification, pathologists can look for evidence of cell death (necrosis), different kinds of invading white blood cells, actual virus particles (inclusions), or bacteria. Some diseases cause such specific lesions (pathognomonic lesions in pathologists’ lingo), that the diagnosis can be made on histopathology alone, without additional testing. Pathologists also can request a number of special stains that are applied to the slides and highlight only specific pathogens or lesions to help identify cause of death or disease in an animal.

About 30% of the time, we can't determine what caused an animal's death, but histopathology can help tell the story of what happened to an animal, when the animal can't tell us themselves.