HPAI Update 1/21/26

Avian influenza virus infections follow a seasonal pattern tied to bird migration, with cases peaking in late fall and winter. HPAI has been detected in 13 counties in raptors and waterfowl and one striped skunk. The Wildlife Health Program began receiving reports of larger mortality events (20+ birds) in Regions 3 and 8 in the fall of 2025. In Region 8, these cases spiked in early December with a steadily increasing number of calls from the public about suspected and confirmed HPAI birds.

Reports include multiple incidents involving large groups of geese that could not be collected due to their location. Reports of public interactions with sick wildlife have also increased. We have found H5N1 in nearly 290 birds across 35 species this year, with waterfowl and raptors being the most affected.

For more information on HPAI, visit our Avian Influenza disease page with a printable fact sheet.

If you find dead birds, especially multiple species or individuals in one place, please report it by clicking the button below.

NYSDEC Avian Influenza Reporting Form

And:

- Limit contact unless necessary, and keep children and pets away

- If carcasses need to be removed, use a shovel if available, and wear disposable gloves, a mask, and eye protection; wash hands and clothing immediately after

- Triple-bag carcasses and put them in an outdoor trash receptacle

In addition to wild birds, HPAI has also been confirmed in wild mammals in New York, with 39 cases across eight species, including red foxes, raccoons, a striped skunk, a Virginia opossum, and a bobcat. New York had the first confirmed positive cases of HPAI in an Eastern gray squirrel and a muskrat. There has been a wider range of mammals, particularly carnivores, in other parts of the United States.

This interactive map displays the counties in New York where highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) was detected in 2025 by the NYS Wildlife Health Program.

Avian Influenza Background

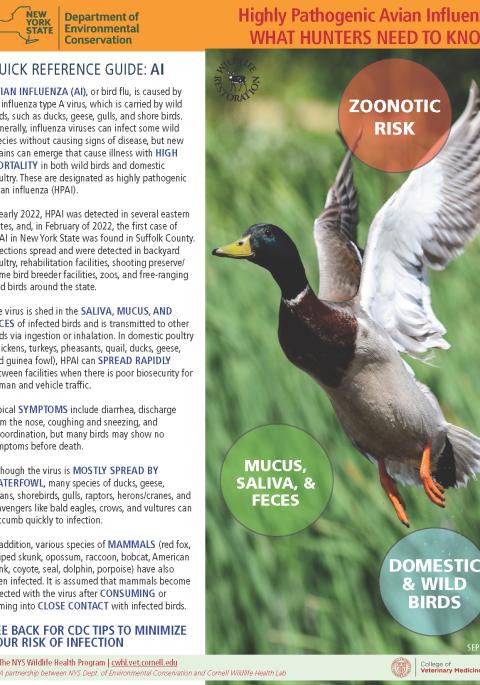

Since late November 2021, numerous outbreaks of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) have been detected in the United States and Canada in both wild and domestic birds. Avian influenza (AI) is caused by an influenza type A virus, which is carried by free flying wild birds such as ducks, geese, gulls, and shore birds. Generally, influenza viruses can infect some wild species without causing signs of disease, but new strains can emerge that cause illness with high mortality in both wild birds and domestic poultry. These are designated as HPAI.

This HPAI strain is type H5N1 2.3.4.4.b, and likely came from Europe where it has been circulating since 2020-2021. The start to this outbreak has been a “slow burn” with rapid expansion of cases in mid-March. As of 17 March 2022, there were 376 detections in 23 states in both wild birds and poultry; all 4 flyways have had detections in a variety of species.

The primary source of surveillance in the U.S. is USDA-Wildlife Services, which expanded their planned surveillance from Atlantic and Pacific flyways to also sample the Mississippi and Central flyways. The Atlantic flyway surveillance was successful because HPAI was detected in wild birds before poultry cases appeared. Confirmed cases are listed on the USDA website and shown on the USGS map.

HPAI Update 11/12/25

In New York, this summer was quiet, with few to no cases of HPAI. The fall season started with multiple mass mortality events in black vultures. There have been three separate black vulture die-offs starting in early September: 50 found deceased in one incident in Rockland County, 12 found dead in Orange County, and 14 found dead in Westchester County. This seasonality of disease cases is associated with Fall migration, leading to an uptick in cases as waterfowl move south. This increase is expected to continue through winter and spring migration. We have found H5N1 in nearly 290 birds across 35 species this year, with waterfowl and raptors being the most affected.

HPAI Update 04/17/25

In New York, 2025 started off with an increase in bird cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). We found H5N1 in nearly 250 birds across 30 species thus far, waterfowl and raptors being the most affected.

In addition to wild birds, HPAI has also been confirmed in wild mammals in New York, with over 30 cases across eight species, including red foxes, raccoons, a striped skunk, a Virginia opossum, and a bobcat. New York recently had the first confirmed positive cases of HPAI in an Eastern gray squirrel and a muskrat. There has been a wider range of mammals, particularly carnivores, in other parts of the United States.

HPAI Update 4/16/24

Highly pathogenic avian influenza has been confirmed in dairy cows from Texas, Kansas, Michigan, New Mexico, South Dakota, Idaho, North Carolina, and Ohio. This is the same H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b that has been circulating in the U.S. since January 2022 and globally since 2021. The initial transmission to dairy cattle is thought to have occurred through wild birds. Additionally, evidence shows the virus was spread by cattle movements between herds and potential interaction with nearby poultry premises. Shared milking equipment is also a suspected route of transmission. Infected animals have decreased milk quality and quantity. Pasteurized milk is still considered safe to consume.

For more information, visit USDA APHIS: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) Detections in Livestock

HPAI Update 1/8/24

In New York, 2023 marked the second year of highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks. First introduced into North America via Canada in late 2021, the HPAI virus H5N1 2.3.4.4.b has moved across the U.S. with multiple, separate introductions occurring on both coasts. Domestic poultry operations continue to be impacted most severely with 341 detections across 25 states. New York had 12 poultry detections in flocks and live bird markets. For wild birds, 2,625 cases were reported across 48 states with New York at 100 birds. California, Colorado, Oregon, Illinois, North Dakota, and Alaska all had more detections. There were 89 species identified with confirmed infections. Most common were mallards, American green-winged teal, Canada goose, bald eagle, blue-winged teal, gadwall, American wigeon, red-tailed hawk, northern pintail, black vultures, and snow geese. In New York, the trend was similar with mallards (n=34), red-tailed hawk (13), Canada goose (11), bald eagle (10), American crow (9), snow goose (8), peregrine falcon (4), great black-backed gull (3), and 1 each for barred owl, common raven, double-crested cormorant, great horned owl, northern pintail, red-shouldered hawk, trumpeter swan, and turkey vulture. For wild mammals, there were 89 detections in 12 species across 20 states with New York having 11 cases. There were red fox (9), striped skunk (1), and a Virginia opossum (1). Other states documented cases of raccoons, bobcats, harbor seals, blackbeards, fisher, and marten, which are all species that occur in New York.

Samples were collected by state wildlife agencies and USDA-Wildlife Services. Data provided represents all cases submitted to the USDA-National Veterinary Services Laboratory. Data summaries provided by Dr. Hon Ip, USGS-National Wildlife Health Center.

HPAI Update 3/9/23

A striped skunk was found dead in proximity to deceased Canada geese in late February in Tompkins County. The skunk and one Canada goose were collected and submitted for diagnostic evaluation. Both animals tested positive for HPAI (H5N1). This is the first skunk to test positive for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in NYS. The H5N1 strain in both animals was detected using Molecular testing at Cornell's Veterinary Diagnostic lab and confirmed by the National Veterinary Service Lab (NVSL) in Aimes, Iowa.

HPAI Update 1/17/23

While poultry and wild bird species are still being devastated by highly pathogenic avian influenza, reports of additional mammal species beyond red foxes are testing positive for avian influenza, including skunks, bobcats, and fishers. USDA data shows avian flu spread to red foxes, skunk in Minnesota

HPAI Update 6/9/22

H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza has been detected in several red fox kits that were submitted to wildlife rehabilitators from three separate Counties in NY. The fox kits exhibited neurologic signs including tremors, apparent blindness, or lethargy prior to death. This is the same strain that is currently affecting wild and domestic birds in the US and Canada; infected red fox kits have also been detected in MI, WI, IA, MN, and Ontario. No adult foxes have been found to be infected as of yet.

Biosecurity, including quarantine of new carnivore arrivals, is recommended. The reported behavior and signs in the HPAI-infected fox kits are also the same as those expected for rabies-infected foxes. So far no other HPAI-infected mammal species have been detected in North America but it is assumed that others are likely susceptible. The Wildlife Health Program is currently interested in examining neurologic foxes, other canids, mustelids, and aquatic rodents to see if any other species are infected.

Domestic Poultry Risks

When transmitted to domestic poultry (chickens, turkeys, pheasants, quail, ducks, geese, and guinea fowl), HPAI can spread rapidly between facilities when there is poor biosecurity for human and vehicle traffic. Typical symptoms include diarrhea, discharge from the nose, coughing and sneezing, and incoordination, but many birds may show no symptoms before death. States with HPAI are prohibited from exporting any poultry products and infected farms are depopulated rapidly to contain the disease.

Status of HPAI in New York

Cases in New York were first confirmed in February 2022 in Suffolk County and are continuing in backyard poultry, rehabilitation facilities, shooting preserve/game bird breeder facilities, zoos, and free-ranging wild birds around the state. The USDA and NYS Department of Agriculture and Markets will be leading the disease response in infected domestic birds (including captive gamebirds), but there is no way to contain the infection in wild birds other than to remove bird carcasses that have succumbed to HPAI. Poultry and gamebird facilities, rehabilitators, falconers, and backyard flock owners have been advised to increase biosecurity measures to prevent transmission. Falconers should avoid having their birds consume any at-risk species including waterfowl and shore birds. At this point, we should assume HPAI can show up anywhere in New York.

DEC’s Reynolds Game Farm works closely with Cornell University on biosecurity issues and they have been in consult during the recent HPAI outbreak. The game farm is enrolled in USDA APHIS Veterinary Service’s National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) program, and as a part of that they receive AI testing regularly. Staff visiting the farm should follow all biosecurity protocols. If you keep backyard poultry or other birds you should change clothing and shoes, shower, and disinfect any equipment used before visiting. The same precautions should be taken between visiting the farm and returning home.

Although the virus is mostly spread by waterfowl, many species of ducks, geese, swans, shorebirds, gulls, raptors, herons/cranes, and scavengers like bald eagles, crows, and vultures can succumb quickly to infection. In our efforts to keep track of wildlife HPAI cases and provide an early warning to NYSDAM and local poultry or gamebird operations, we would like to examine any unusual mortalities of the species listed above. Passerines do not seem susceptible to HPAI and are not thought to play a significant role in spreading this virus. We are not recommending removal of bird feeders at this point.

Wild birds confirmed as infected in New York include snow goose, Canada goose, tundra swan, mute swan, sanderling, black skimmer, Caspian tern, herring gull, great black-backed gull, American black duck, American wigeon, gadwall, green-winged teal, lesser scaup, mallard duck, northern pintail, northern shoveler, redhead duck, ring-necked duck, wood duck, pied-billed grebe, hooded merganser, common loon, great blue heron, double-crested cormorant, bald eagles, peregrine falcon, merlin, barred owl, eastern screech owl, great horned owl, snowy owl, cooper’s hawk, red-shouldered hawk, red-tailed hawk, American crow, common raven, fish crow, ruffed grouse, Black vulture, and turkey vulture.

Recommendations for DEC Field Staff - please visit HPAI Guidance for DEC Field Staff

Risk of HPAI infection for humans:

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) states that the health risk from this strain of bird flu virus is low, “however some people may have job-related or recreational exposures to birds that put them at higher risk of infection.” Follow the above precautions when handling wild birds, particularly waterfowl, gulls and raptors, to reduce your risk. Consider receiving seasonal influenza vaccines. Monitor your health for any signs of flu-like symptoms within a week of handling wild birds and consult your health care provider if you have any questions.

Further Information:

USDA Backyard Poultry and Biosecurity

USDA APHIS: Protecting Captive Wild Birds From Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza